Common Artist Questions Answered

Q: I keep sending images of my art out to galleries and no one is interested. What am I doing wrong?

A: If you randomly send info and images of your art to galleries you don't know or who don't know you, and who aren't familiar with your work, this won't be productive and chances are slim that they'll pay any attention at all. Or if you send your art to out-of-town galleries without first establishing a reputation online or a local or regional reputation in the art community where you live, this likely won't be productive either.

Instead, begin by using social media in combination with regularly getting out into your art community. Identify specific galleries where you would like to show, make sure they sell art that's similar to yours, follow them on social media, get on their email announcement lists, and when possible, visit them in person, attend their openings, and otherwise keep tabs on what they're up to. If you do get the opportunity to speak, contact, or communicate with them, be able to state clearly and concisely what you admire about them, what your intentions are, and why you believe your art is right for them.

Q: How can I find an agent to represent my art?

A: The "artist agent" is basically a myth. Art dealers and galleries represent artists-- that's about the closest thing to agents in artland, and they're the ones you should be contacting. A small percentage of artists have what you could call agents or representatives-- more like managers really-- but these artists tend to be very successful and established in their careers, generate lots of sales, and are so overwhelmed with dealer, gallery, museum, and collector requests that they hire professionals to handle their business affairs.

Q: I've been making art for several years and have been in a couple of group shows at local galleries. Should I contact major galleries and try to get shows?

A: Let me ask you a question. If you're in a band that occasionally plays local bars and nightclubs, should you try to get a gig at Madison Square Garden? The art world is like anywhere else. You work your way up; you can't skip steps.

Q: Should I make limited edition giclees or digital prints of my art?

A: Yes, if you've got significant name recognition, your art is in demand, or your originals have gotten so expensive that only well-healed buyers can afford them. Many people who can't afford originals by established artists they love will buy affordable digital prints if given the opportunity. They're fans of the artist, follow them on social media, or see their shows. Maybe some of their friends own prints, and they want one too. Keep in mind that if you're not well known, don't make a lot of sales, and have plenty of originals available, a significant downside to selling prints of your art is that you can end up competing against yourself. In other words, people will opt for your cheaper limited edition prints rather than your more expensive originals.

Q: Should I invest in a website to show my art?

A: Absolutely. No matter how active you are on social media or what kind of an online profile you have, the only place on the Internet where you are in total control is your website. Not having your own website is risky business if your only online presence is on other people's platforms; they can change the rules anytime they feel like it and you can't do a thing about it. As for your site, just don't pay a lot for it (unless you're rolling in bucks). There are plenty of very affordable DIY options these days like Squarespace, Wix, and Weebly where you can pretty much design and run everything yourself.

If you're not well known, do what you can to drive traffic to your site, but don't expect to make instant sales. The main purpose is to have your art organized and presented so anyone who visits can get a good sense of who you are and what you're capable of. The problem with getting traction for a new site is that people who don't know who you are can't type your name into search engines or search you on social media. Best procedure is to design a basic website and get the word however you can-- on social media, by making your presence known in your local or regional art community, and by showing your work in public whenever you get the chance.

A good starter website should include images of your art that are organized into related groups or series, your statement, bio, resume, social media pages, and contact information. And no fancy tricks like flash, sound, windows that take too long to open, or other interface gimmicks that slow visitors down. When I go to an artist's website, I want to see on thing only-- the art-- and learn about it and the artist as quick and easy as possible.

Q: Should I set up a store to sell my art on my website or anywhere else online?

A: Stores can be expensive to set up and maintain, and aren't really practical for most artists, especially those who sell only originals. You may even pay percentages of sales to whoever hosts them. As if all that's not bad enough, most of them are cold, impersonal, button-click interfaces that often make the art look more like product than handmade objects created with love, care, purpose, meaning, and significance.

In the art world, most buyers prefer the personal touch, not impersonal online transactions like those at online art stores. They really like to communicate with artists first, ask questions, understand what they're getting, establish rapports, see other works similar to the types they're interested in, go over details, and so on.

Instead of a store, accept payment direct like through credit cards, PayPal, Venmo, etc. That's really all you need. And make yourself accessible and available to potential buyers or anyone else who wants to know more about your work. The best part? You can save all kinds of money at the very same time.

Q: Should I set up pages or galleries on large art websites like Saatchi, Etsy or Fine Art America?

A: Now that we have social media, those types of platforms are largely out of date. They made sense in the early days of the Internet when art and artists were hard to search or find online, and were pretty much the only game in town when it came to seeing large searchable selections of art by many artists all in one place. Social media sites now give artists as well as collectors far greater access to whatever they're looking for than any big artist website. On Instagram, for example, hashtags allow artists to categorize, label, and place their art in specific "galleries" or locations. Hashtags also allow buyers to find exactly the types of art they're looking for. The best part? Social media sites are free whereas big art websites often charge for gallery space or take significant commissions on sales.

Other problems with big art websites is that they're designed mainly to make money for their owners and not necessarily for the artists who sell on them. Sure, they sell art, but they don't care whose art it is. For example, if a prospective buyer lands in your gallery, the site will suggest options to see similar art by other artists. There's little or no incentive for that buyer to stay in your gallery.

And then there's the numbers; most large sites offer many thousands of artworks by many hundreds of artists, and sometimes much much more. With all that competition, an artist selling a piece of art is like hitting a jackpot in Vegas. The odds may be better if a site agrees to feature the art or artist on a regular basis, but most artists are just one of the herd. Lastly, artists on social media have much greater control over how they organize, present and promote their art whereas on bulk art sites, they have to abide by strict rules of display, promotion and sales procedures.

Q: Should I pay for shows or to rent wall space at galleries that charge fees?

A: Depends on the gallery. Some are genuinely artist friendly or are run by artists, charge reasonable fees, and perform valuable services for their area art communities by providing aspiring artists with venues to show. Others are expensive, out for themselves, make big promises, and deliver little or nothing. Best way to research this type of gallery is to speak with artists who currently and have previously shown at these places BEFORE you fill out applications or make any committments to pay for space.

Q: I get occasional offers to submit my work to directories of contemporary artists that say they print thousands of copies for national or international distribution. Submission may be free or nominal in cost, but if I'm accepted, costs to be included can range as high as several thousand dollars. In return, I can get a page or two-page essay about my art and anywhere from two to five illustrations. Yes or no?

A: No. Established respected directories like Who's Who in American Art (Marquis Who's Who) or New American Paintings (Open Studios Press) do not charge to be included-- you have to be accepted, though, and that's not easy (New American Paintings charges a nominal submission fee; Who's Who in American Art charges no fees). Those that charge for inclusion have to be researched in advance to make sure people have heard of them, they have decent circulations, and have credibility in the art community. If they don't, forget it.

Unfortunately, a number of these publications are more about vanity and making money for themselves than advancing artists' careers, and if you apply, you can bet you'll get in. Why? Because that means you get to pay them hundreds or thousands of dollars to be included. They have zero incentive to turn you down. And while we're on the subject, what incentive do they have to actively sell or distribute their publication? They've already been paid by the artists they include. Plus this-- for the kind of money some of these publications charge, you can buy a display ad in a major glossy national or international art magazine, or build yourself a serious website.

Q: Can you give me some names of galleries, collectors, or agents that would be interested in my art?

A: The idea that someone established in the art business is supposed to give total strangers contact information of people they've know for years or even decades is absurd. To begin with, they have absolutely no idea who you are, what you're like as a person, what you're capable of as an artist, or how you are to work with. The way the art world operates is that people only refer artists who they already know, respect, and believe in-- and they only refer them to dealers or galleries who they already know (and who already know them).

Art business relationships are built on trust, experience, familiarity, and mutually beneficial involvements over time. No one wants to jeopardize their standing, reputation or contacts in the art community by arbitrarily giving out names and numbers of friends or business associates to artists they don't know. When referrals are made, they're made for specific reasons, with specific intentions, with specific outcomes in mind, and between people who already know and trust each other.

Q: Everybody loves my art. How come I can't sell any?

A: Depends on your definition of "everybody." If you're talking friends and family, they love whatever you do (and even if they didn't, they wouldn't tell you). Try this-- next time "everybody" starts gushing about your art, ask which pieces they'd like to buy and how they'd like to pay for them. Love means lots of different things to lots of different people, but in the art business, love means $$$.

Another thing to consider is whether your prices make sense. Can you explain them to potential buyers in ways they can understand and appreciate? Are they comparable to those of artists who have similar career accomplishments, live in your area, and make art that's similar to yours? Increasing sales may simply be a matter of making your art more affordable to a wider range of potential buyers.

Q: Should I buy mailing or email lists of galleries and then send out introductory information about my art?

A: Mailing or email lists are almost always a waste of money-- and the art world's version of spam. You have no idea how these lists were assembled, what kinds of galleries or individuals are on them, what kinds of art they deal in, whether your art is even remotely right for them, etc. etc. etc. If you have no idea who your contacting, sending them your information is no different than walking up to a total stranger and asking them to look at or buy your art. Not only do galleries get these kinds of random communications from artists they've never heard of all the time, but they're also really good at spotting mail or email spam. You stand a far better chance of having your mailings end up in the trash or deleted than you do of them opening it up and looking at it. Best procedure is to research galleries you think might have interest in your art and contact them one by one.

Q: I donated a painting to a charity auction and it sold really high. So I raised all my prices. Now I can't sell anything. What's the deal?

A: The money went to charity, not to your art. Charity auction selling prices often have little to do with the value of what's being sold-- items sell way too low and way too high all the time. Many people who bid at charity auctions see it like this-- they donate money they intend to donate anyway, except that when they donate it at an auction, they get free stuff in return (aka your art).

Q: Is it best to let my art speak for itself rather than say anything about it?

A: Yes, but only if you make talking art. Otherwise, you have to speak (or write) for it-- provide basic information about it-- so that viewers can better understand, appreciate, and connect with what you're doing. Knowing something about art rather than nothing is like the difference between watching a play with actors dressed in street clothes in a bare room, and then watching the same play on a stage with actors in full costume and the stage fully set. The script is exactly the same in both cases, but your depth of appreciation, understanding and involvement with the experience is far greater when you have access to more information about it than less... or none.

Q: Do I need to explain my art in terms of art history and talk about where it fits in?

A: Not really. About the only time you get into that is when someone who understands art history asks. Most people know very little about art history. And of the few who do know, most can figure out where your art fits in for themselves. What they want to hear is your story-- why you've dedicated your life to making art, what inspires you, how you've chosen to express yourself through your art, what you strive to communicate through your work, how you make your art, why it looks the way it does, what it represents, and how it conveys your commitment, beliefs, feelings, and opinions. A good honest story beats an arcane disquisition on art history approximately 100% of the time.

Q: Should I mention names of important artists who influenced me when I talk or write about my art?

A: No. For example, if you say your art is influenced by Warhol, the attention is immediately off you and on Warhol. By invoking famous names, you leave yourself and your art open to being compared with those names, and who do you think is going to win that battle? Certainly not you. It's your art and you're the one who made it, so keep the focus on you. Let the critics and knowledgeable people drop names on your behalf; that's their job, not yours.

Q: My art professors tell me that the way to succeed as an artist is to "go forth and make art." Is that right?

A: Professors who gaslight their students with that kind of crap should be more honest and tell the truth, which is that they don't know how to succeed because nobody ever taught them, and if they did know, many of them wouldn't be teaching. Now I'm not knocking professors here; we need you dearly and teaching is an eminently essential and honorable profession. All I'm saying is that it's OK to admit you don't know something when you don't know it instead of getting all noble and "go forthy" about it to insulate your egos.

The truth is that any artist can learn how to navigate the art world. So many artists at all stages of their careers make so many obvious mistakes that they would never otherwise make if only they had basic training in art school about how the art world works. Once a work of art is complete and ready to leave the studio, it's subject to pretty much the same market forces as any other product. Art business education is essential because learning how to sell art means being able to survive as an artist. You can only travel the road to creative success if you can afford to buy the gas. Hopefully, more and more art schools will teach how art and money mix so that their artist graduates will be able to thrive and prosper from their art.

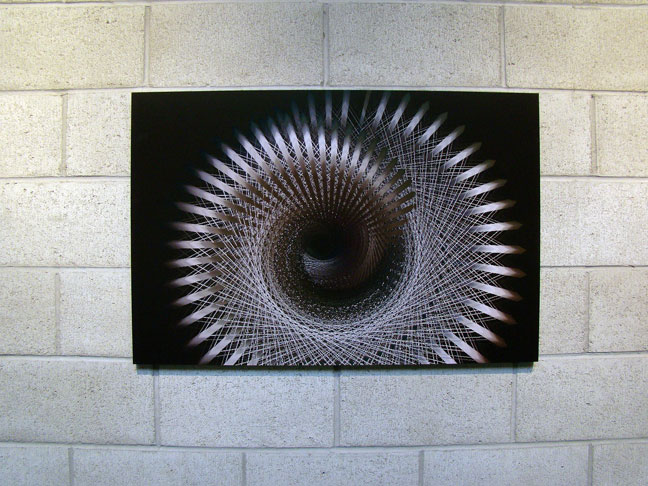

(art by Antonio Cortez)

Current Features

- How to Buy Art on Instagram and Facebook

More and more people are buying more and more art online all the time, not only from artist websites or online stores, but perhaps even more so, on social media ... - Collect Art Like a Pro

In order to collect art intelligently, you have to master two basic skills. The first is being able to... - San Francisco Art Galleries >>